Designing the database first

Usually in agile development, database schemas evolve as applications are written. When the usual phases of delivery specified in the service manual are followed, teams have plenty of time with a limited audience to refactor and refine their work before opening it up to the masses.

The Early Careers Framework (ECF) application didn’t have that luxury. Within 8 months of the first line of code being written every school in the country was invited to register.

Once database choices have been made, are in production and used daily by thousands of people, it becomes very difficult to change them. The initial rush left us with a data model that wasn’t the right fit and every attempt to fix it has resulted in other things breaking.

As a result, over the last 3 years we have spent lots of time reacting to problems caused by the data model.

We’ve had to build tools to help us fix data, pepper links to support forms throughout the interface and spend a huge amount of time optimising our API to prevent our providers from experiencing timeouts.

Rebuilding ECF

The data requirements for ECF are much more complicated than most services in the Department for Education (DfE), which are one-off transactions. ECF induction takes at least two years during that time any number of events can happen which have an impact on the participant, their training and the way providers are paid.

For example, during a participant’s induction they might change school, change from one type of programme to another, switch lead provider, or pause their induction due to illness. Or they could do all of these things, multiple times.

We need to ensure that our new database model can cope with these scenarios.

Testing the model before writing the code will tell us sooner whether or not it will work, and it allows us to quickly iterate on our designs to cover all eventualities. Iterating database designs without having to keep code in sync is fast.

Data outlives code1 so it is important that we can accurately represent the most complex of induction histories in a way future custodians of this service understand.

Prototypes, prototypes, prototypes

Prototyping is the most important step when approaching a difficult problem. It gives you a chance to test various approaches in realistic scenarios to see how they hold up. Getting feedback early prevents you from finding out things don’t work after you’ve built them.

When it comes to prototypes in a GOV.UK setting, most people think about user interface prototypes made using the prototype kit, often in the alpha phase of a project.

Here though, we are in an unusual situation. We are rebuilding an existing application and have identified the database as being the weakest part. We know what data flows in and what flows out. We just need to find a better way of organising what we store.

The database forms the foundations of the application, we need to make sure it’s right or everything we build on top will suffer. Foundations are difficult to change once the house is built.

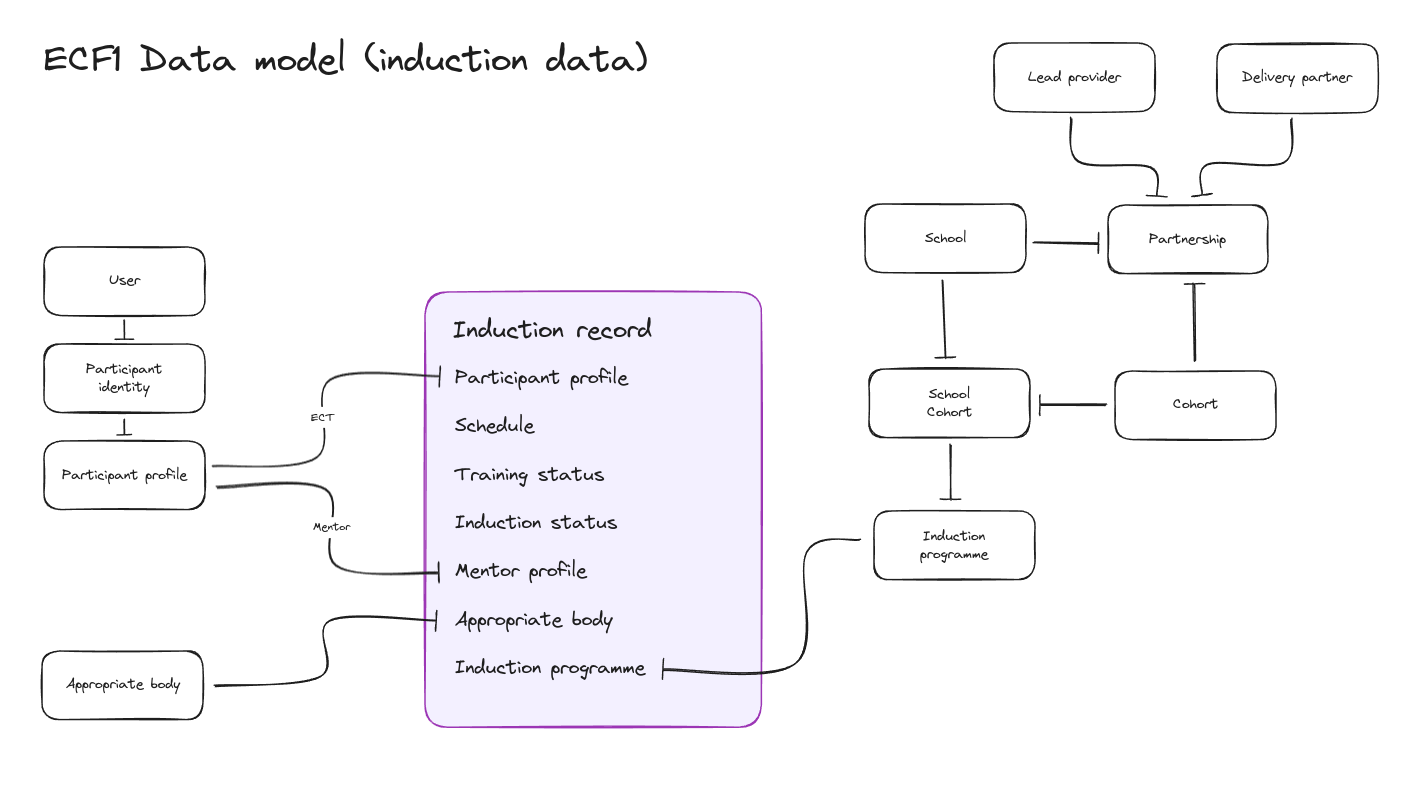

One of the main problems we faced with the current version of the ECF application is that we hold an early career teacher’s (ECT) entire training and induction history in a single place — the induction record.

Complexities with induction records

The induction record table is append only, meaning that changes are recorded as new rows instead of existing rows being updated. It also stores future events, like a proposed change of school that may happen at some point in the future. This approach means finding the right induction record isn’t trivial, we need to ensure we have the latest that isn’t in the future.

To complicate matters further, only relevant parties can see parts of the induction record that belong to them.

Finding a better way

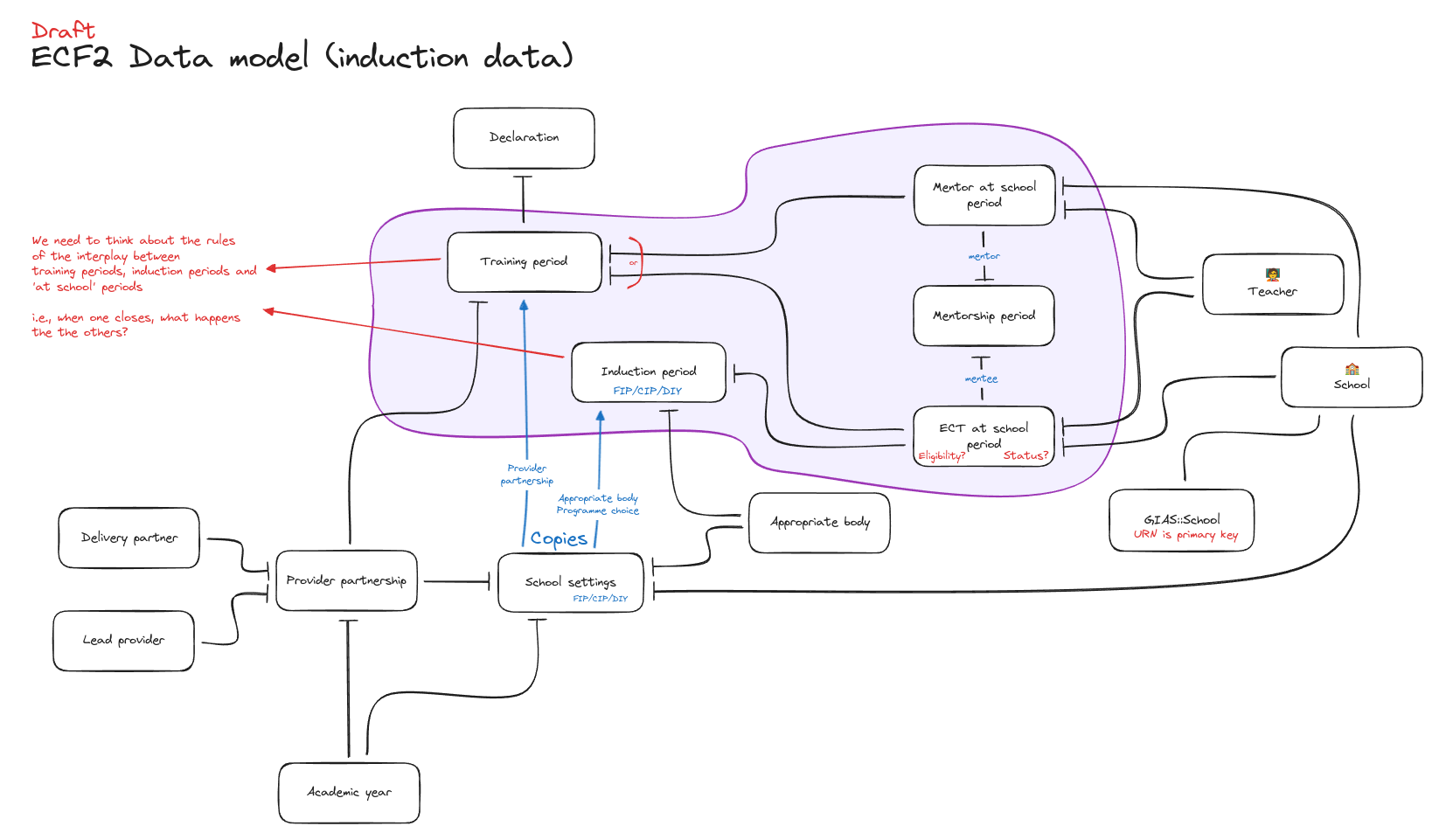

We first started seriously thinking about how to better record training and induction data in August 2023 and held a workshop where we came up with several schema ideas and discussed them at length. Later we whittled them down to one, a model which stored each kind of data separately.

Holding each kind of data in its own table has several advantages:

- when something changes we only need to update the corresponding table

- more of the model is routed in reality

- the final schema is much more normalised which reduces repetition and makes it easier to keep things accurate and consistent

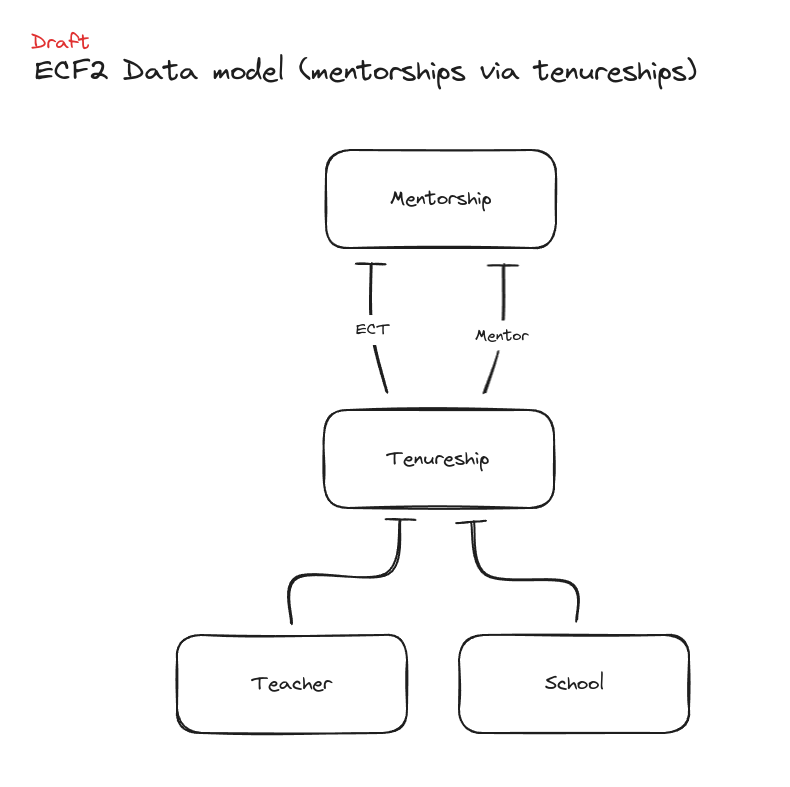

However, when we tried to create realistic complicated scenarios with the separated model, some things still didn’t quite work. Namely, the idea of a tenureships model which tracks which teachers were at which schools over time, regardless of whether they were at the school as an ECT or mentor, was confusing.

Not only did the name ‘tenureship’ confuse people on the team, it demonstrated that trying to store both ECT and mentor data in the same place wasn’t right.

A teacher can be an ECT at just one school at a time, but a mentor can mentor at many schools at once.

With this schema we’d have to add extra validation logic to cope with these requirements. Splitting tenureships into two tables, one for ECTs and one for mentors, was much cleaner.

The current situation

Now we have a model we’re fairly confident in. It’s coped well with the scenarios we’ve thrown at it and has been scrutinised by lots of people across the CPD programme.

It’s definitely not done yet, we’ll continue to refine it as the application is developed. Doing these many iterations now, before we have an application and data to migrate, has been a rewarding exercise. It’s given us confidence that the most complex part of the data model has been carefully planned, tested, and is robust enough to stand up to the expectations of our providers and users.